Conservatives' "Talking Filibuster" Scheme Isn't the Norm in the Senate

The SAVE Act may make hyperpartisanship worse

Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD) has ensured a vote on the SAVE Act, presumably the version recently passed by the House, S. 1383. That vote could happen as soon as next week. The unanswered question right now is the process for the bill. Will Thune proceed under Rule XXII—the modern, predictable process that allows debate to end while the Senate continues functioning—or will he indulge conservatives’ preference for a “talking filibuster,” a tactic that trades procedural purity for prolonged floor paralysis?

Conservatives want you to believe that the “talking filibuster” is the norm in the Senate. This is misleading. What these conservatives aren’t describing is how the Senate actually works today. Before the adoption of the cloture motion in 1917—found in Rule XXII of the Standing Rules of the Senate—there wasn’t a way to force an end to debate. Prior to 1917, senators could use various tactics to stop a bill from moving forward, ranging from objecting to unanimous consent to engaging in a talking filibuster.

What we think of as the modern-day filibuster—the cloture motion—was created out of necessity during World War I, after the Senate proved incapable of ending debate on critical wartime legislation. As one of the rule’s primary opponents, Sen. Lawrence Sherman (R-IL), put it, cloture was adopted because of “the failure to pass the armed merchant ship bill,” the Wilson administration’s proposal to arm American merchant ships after German U-boats sank the Housatonic and Lyman M. Law. Although the rule was adopted in 1917, it would not be successfully invoked until 1919, when the Senate used it to limit debate on the Treaty of Versailles.1

Cloture motions went from being used sparingly from its creation in 1917 to being the norm. From 1917 to 1970, cloture motions were filed only 58 times. Cloture was invoked in just eight of those instances. Over time, despite the creation of a two-track system and a reduction in the number of votes required to limit debate, cloture motions were used more often to break the gridlock in the Senate. That gridlock is a result of obstruction caused hyperpartisanship. Both parties are responsible for it.

The “talking filibuster is the norm” line doesn’t really have any basis in fact. That doesn’t, however, mean it’s an abuse of the rules. It’s a literal interpretation of them. Still, a literal interpretation is not the same thing as a neutral one. Enforcing a talking filibuster exploits procedural design in ways the Senate never intended to sustain indefinitely. What would this look like? Republicans would bring the SAVE Act to the floor. The presiding officer would ask if any senator seeks recognition to speak. Democrats would respond by beginning debate on the bill.

Under Rule XIX, each senator can give two speeches on the same question each legislative day. Speeches aren’t time-limited. As Matt Glassman notes, “Imagine all 47 Dems making two 3-hour speeches. That’s totally plausible. That’s 288 hours. And that’s just to get to a majority-rules vote on the motion to proceed[.]” It may be an extreme example, but I agree that it’s plausible. Nevertheless, 288 hours is equivalent to 12 calendar days.2 That’s only on one question. It doesn’t include debate on amendments or on the bill, each of which is a question before the Senate and provides every member of the Senate Democratic Caucus the opportunity to make two speeches.

We can’t say for certain how many questions there would be for the Senate to consider. We know for a fact there would be two. The motion to proceed and final passage. Using Glassman’s example—two three-hour speeches per Democratic senator—you’re looking at 24 calendar days. Now, add in amendments. Oh, and Democrats wouldn’t have to worry about amendments being germane. This means Democrats could force politically tough votes for Republicans.

Republicans believe that forcing Democrats to hold the floor for potentially days at a time will have a political cost. Republicans will point to Democratic obstruction, but Republicans will pay a price as well. Democrats can force Republicans to maintain a quorum on the floor. The entire strategy of the “talking filibuster” also guarantees that the Senate floor will grind to a halt. Thune or his designee could move nominees to the Executive Calendar for work, but the Legislative Calendar would remain impassable until work on the SAVE Act is complete. It’s not a stretch at all to say that this effort could take weeks. It could even take months, depending on the Democrats’ resolve.

During this time, Democrats will almost certainly use the Senate floor to keep public attention focused on the SAVE Act’s most politically vulnerable provisions, including requirements that could complicate voter registration for married women and mandate the transfer of voter data to the Department of Homeland Security. Republicans may view documentary proof of citizenship as energizing to their base and point to polling showing broad support for voter photo ID requirements. That said, base enthusiasm and favorable polling are not the same as electoral salience. There’s little evidence that these issues, standing alone, will drive persuasion among undecided voters in a midterm election.

That does not mean the politics cut in Republicans’ favor. While independents are more likely to prioritize inflation, the economy, and healthcare, election administration framed as a threat to democratic participation can function as a powerful mobilizing issue. Concerns about threats to democracy did not change many minds in Virginia in November 2025, but they did mobilize voters who might otherwise have stayed home, according to research from Virginia Commonwealth University. A similar dynamic could emerge nationally in 2026 if Republicans appear unwilling to check the expansive claims of power coming from the Trump administration.

The bottom line is the SAVE Act won’t be easy to pass. The “talking filibuster” isn’t the norm that conservatives are claiming it is, and it would take weeks or even months to pass the SAVE Act under this scenario. It would also escalate tensions in the Senate, making it harder for bipartisan cooperation on any meaningful issue.

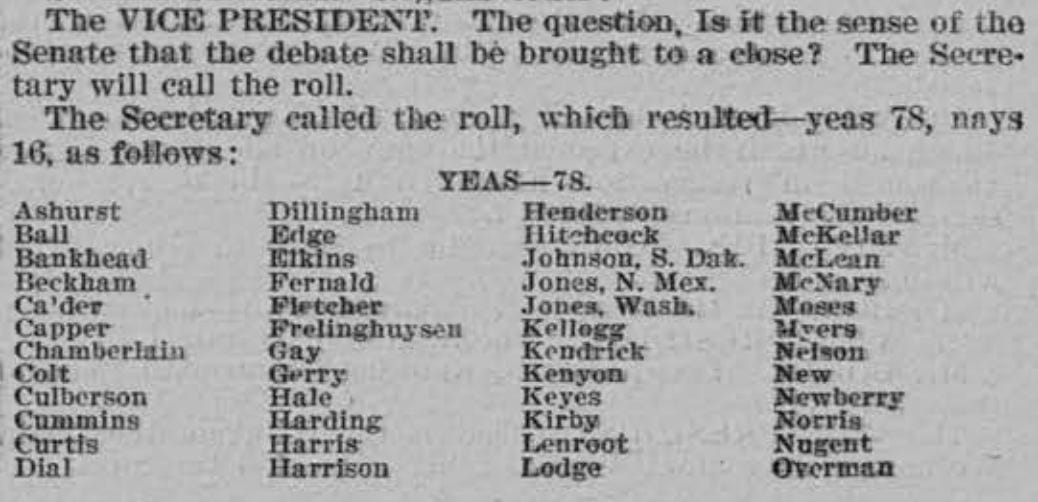

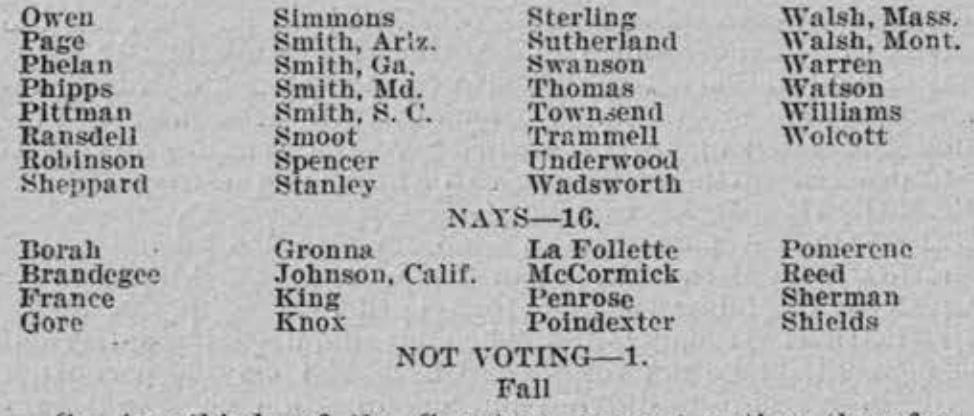

The vote on the cloture motion can be found on p. 11-12 of the PDF. The vote was 78 to 16.

The longest legislative day in recent memory was 22 calendar days—January 3, 2019 to January 24, 2019. This doesn’t mean a continuous session. The Senate met during this stretch but recessed rather than adjourned. It’s an important distinction in Senate parlance.