The SAVE Act Presents Creates Paperwork Burdens for Some Voters

The conservative-backed bill may also institute an unconstitutional poll tax

As the so-called “SAVE Act”1 gets more attention, more people are beginning to wonder what it could mean for them. Because of the nature of what I do for a living, some friends have reached out to ask about the bill. They’re seeing posts about it online, and those posts often have conflicting messaging. Supporters of the SAVE Act claim the legislation is just a voter ID bill, citing polling showing that 80 percent of voters support such a policy. However, there’s a growing concern that the bill would make it harder for people, particularly women who have changed their last name, to register to vote.

Several days ago, I wrote about some of the problems the SAVE Act. Specifically, I explained that the SAVE Act marks a radical shift for Republicans. When I was the vice president for legislative affairs at FreedomWorks, I attended meetings hosted by Republican leadership in 2019 in which they railed against House Democrats’ For the People Act. They complained that various aspects of the bill violated the core tenets of federalism and that others were unconstitutional.

Although the SAVE Act isn’t as comprehensive as the For the People Act, it still encroaches on an area traditionally reserved for the states. Indeed, 36 states have passed some form of voter ID. Some of those states have stricter requirements than others. I would argue that the general premise of the bill—that Congress can legislate an ID requirement to register to vote in federal elections—is constitutional. Article I, Section 4 of the Constitution provides states, “The Times, Places and Manner of holding Elections for Senators and Representatives, shall be prescribed in each State by the Legislature thereof; but the Congress may at any time by Law make or alter such Regulations, except as to the Places of chusing Senators.” Other aspects of the SAVE Act are very problematic and probably unconstitutional.

As I previously noted, I don’t have a problem with voter ID, but I do have concerns about the SAVE Act. Supporters of the SAVE Act are presenting the bill in a way that misleads Americans. The bill isn’t simply a voter ID proposal. The SAVE Act is also based on the false premise of widespread voter fraud. This conspiracy theory has been disproven, time and again. Unfortunately, in an effort to please Trump, Republicans are pushing this bill.

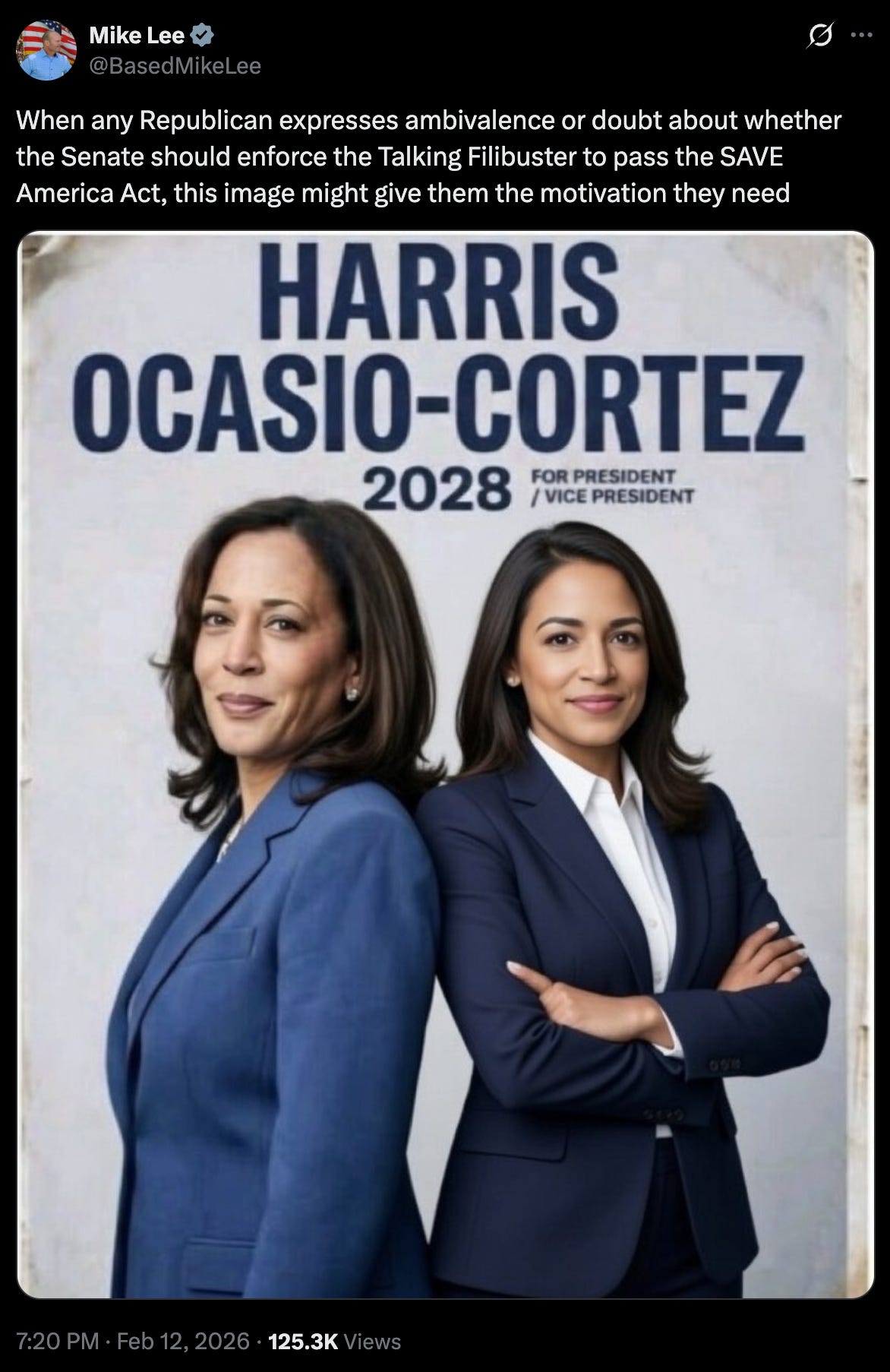

There’s also a concern of voter disenfranchisement. Admittedly, in the past, I’ve tended to dismiss concerns about Republican-backed election proposals, but I do think the SAVE Act is designed, in some way, to reduce the number of people who vote. Recently, I saw a tweet from the main Republican pushing the SAVE Act in the Senate, and it’s hard not to draw the conclusion that he wants to pass the bill, even breaking modern norms in the Senate to do so, to prevent Democrats from winning elections.

What the SAVE Act Requires to Register to Vote

The latest version of the SAVE Act passed the House on February 10. The legislative vehicle for the bill is S. 1383. I’ve seen some posts on social media about the text of H.R. 22 or H.R. 7296. These bills are out of date. The current text is S. 1383. This is the bill that matters. The House amended S. 1383 and sent it back to the Senate because this allows the upper chamber to bypass the initial cloture motion on the motion to proceed.2 The Senate can vote by a simple majority on the motion to proceed to “get on the bill.” What happens next is a separate question, and it deserves a separate post about the “talking filibuster” some conservatives want to pursue to pass the SAVE Act.

The SAVE Act isn’t a voter ID bill in the way we normally think about voter ID. When we hear “voter ID,” we think of going to our polling place and presenting our driver’s license to cast our ballot. Although the SAVE Act does now include a voter ID provision, it also requires proof of citizenship to register to vote. We’re focusing on the voter registration requirements. The person wishing to register to vote has to present one of the following (the bullets are directly from the text of S. 1383):

“A form of identification issued consistent with the requirements of the REAL ID Act of 2005 that indicates the applicant is a citizen of the United States.”

“A valid United States passport.”

“The applicant’s official United States military identification card, together with a United States military record of service showing that the applicant’s place of birth was in the United States.”

“A valid government-issued photo identification card issued by a Federal, State or Tribal government showing that the applicant’s place of birth was in the United States.”

Now, the reference to REAL ID is a legislative sleight of hand. I’ve seen some people online say, “Well, I have a REAL ID, so I’m fine.” That’s incorrect. REAL ID only verifies lawful status, which would include noncitizens lawfully present in the United States. The text in the first bullet point is a reference to Enhanced Drivers Licenses (EDLs) available only in Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Vermont, and Washington. EDLs include verification of United States citizenship. Not everyone with a REAL ID in those five states has EDLs. They’re optional.

If you don’t have any of the forms of ID listed above, you’ll have to provide a form of state-issued ID and one of the following: a birth certificate, a record of birth from a domestic hospital, a final adoption decree showing a domestic birth, a consular report of birth abroad or a report of birth issued by the Secretary of State, a naturalization certificate, or an American Indian Card showing the classification of “KIC.”

If You’ve Changed Your Name

What if you’ve gotten married and changed your name? Although legal name changes can be made by anyone, women are predominantly the ones who change their names when they marry. A rough estimate I’ve seen is that some 85 million people have changed their names. Obviously, someone who has changed their last name is going to have a problem when they present their birth certificate along with a state-issued ID. The name on the birth certificate won’t make the ID. The SAVE Act does provide a path forward, but it’s not without a paperwork burden or cost.

The way to reconcile name discrepancies is “through an additional process established by the State (which shall be subject to any relevant guidance adopted by the Election Assistance Commission).”3 Obviously, none of that exists right now, but it will require “additional documentation as necessary to establish that the name on the documentation is a previous name of the applicant” or an affidavit signed by the applicant attesting that the name on the documentation is a previous name of the applicant.”4 In other words, you have to go document hunting.

You’re not completely out of luck if you don’t have the documents. Subject to state processes, as well as guidance from the Election Assistance Commission, you can sign an attestation under the penalty of perjury that you are a citizen and eligible to vote. In these cases, state and local officials will determine whether or not you’ve satisfied the citizenship requirements to register to vote. You can also present an affidavit.

Now, some people may have all of these documents readily available. I keep my birth certificate and passport in a specific place. I know where those documents are. If you don’t have those documents, for whatever reason, obtaining them comes with a cost. Getting a copy of your birth certificate ranges from $10 to $35, depending on the state. Private vendors will charge up to $60 dollars. If you want to go the route of an affidavit, you’ll have to have that document notarized. That also costs money, unless you are one yourself, know someone who is a notary, or have access to free notary services. This can cost anywhere from $5 to $20, depending on where you go.

The Constitutional Problem

While I think we have to concede the argument that Congress can preempt states to require proof of citizenship to register to vote, the Twenty-Fourth Amendment presents a problem for supporters of the SAVE Act. The amendment says, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote in any primary or other election for President or Vice President, for electors for President or Vice President, or for Senator or Representative in Congress, shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or any State by reason of failure to pay any poll tax or other tax.”

The costs associated with acquiring that documentation could be considered a poll tax. Georgia passed its voter ID law in 2005. It was challenged on the grounds that the voter ID requirement was an unconstitutional poll tax. The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Georgia agreed and issued a preliminary injunction preventing the state from enforcing the requirement. The Georgia General Assembly revised the law to make state-issued IDs free of charge, thus eliminating the conflict with the Twenty-Fourth Amendment. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit upheld the amended voter ID law.5

Ultimately, if the SAVE Act becomes law, the Supreme Court would have to decide whether the proof-of-citizenship requirement constitutes a poll tax. A decision on that may come sooner rather than later because the intent of the authors of the SAVE Act is for the legislation to take effect upon enactment. In other words, it would apply in the 2026 midterm elections. It’s important to note that the requirements of the bill affect individuals who register to vote after enactment.

What Happens Next?

Senate Majority Leader John Thune (R-SD) has indicated that the chamber will vote on the SAVE Act. It’s not clear when that will happen. He’s also indicated that there’s no desire to eliminate the three-fifths threshold under Rule XXII to reduce the threshold for cloture. There’s also skepticism among Republicans of ultilizing the “talking filibuster” strategy that conservatives want to employ. That said, the pressure from the conservative base of the Republican Party to pass the SAVE Act is immense. The Senate version of the SAVE Act has 49 cosponsors. Sen. Susan Collins (R-ME) has also announced her support. That’s 50. Even if the remaining Republicans don’t support the legislation—and the only one I’m aware of who opposes the bill is Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-AK)—50 votes and a tie-breaking vote from the vice president are enough for passage. But that’s only if Republicans force the talking filibuster.

Trump has said that “[t]here will be Voter I.D. for the Midterm Elections, whether approved by Congress or not!” However, Trump lacks constitutional and statutory authority to issue an executive order requiring voter ID. That’s not to say he won’t try it, but the issue will be litigated and likely delayed by injunctions while the matter works its way to the Supreme Court. The question is whether or not the Supreme Court will do anything before the midterms.

The legislation is also known as the “SAVE America Act.”

This is a three-fifths threshold, or 60 senators voting in the affirmative.

I should note that the Election Assistance Commission already exists. It was created in 2002 by the Help America Vote Act.

The SAVE Act explicitly shuts off the Paperwork Reduction Act. The law exists to reduce paperwork burden and error. Excluding voter registration materials allows forms to become longer, more complex, and more prone to rejection. These are effects that will fall most heavily on first-time and low-information voters.

Before the circuit court issued its opinion, the Supreme Court upheld a similar voter ID law in Indiana. The state made ID available for free to get around the poll tax issue. Notably, Justice John Paul Stevens wrote the opinion in this case.